Ancient guide to Building Blocks

(^literally) Exploring olden architectural workmanships.

Briefly,

There are numerous monuments hailed worldwide that are undoubtedly works of great artisanship. We worship a few as the Wonders of the World, and perpetually neglect a few, but I blame the lack of media attention to be the cause of it. A good number of the most notable monuments involve brutal deaths of its artists* due to heavy work and difficult conditions, or simply the tyranny of the ruling mandate.

The construction of the The Great Wall of China included thousands losing their lives from heavy labour and perhaps even a drop from the heights. It is not very surprising, considering what a Sisyphean task it’d be.

There are a few misinterpretations of historical fables as well that take part in this; Taj Mahal is a case as such. I thought it would be interesting to share.

Ancient fables of the Taj Mahal vaguely describe of what follows:

“Shah Jahan had cut the hands of his workers”

There are a few interpretations of this, we do not know which one is true, yet the last one is claimed to be likely probable (of being the true one).

To ensure that no one would replicate the Taj Mahal after his death,

Shah Jahan had ordered to amputate the hands of all artists* involved in the construction of the Taj Mahal;

He ordered to have only the designers of the Mahal to have their hands cut off, and none else;

Shah Jahan in fact had not taken any such aforesaid actions, but instead had formed a contract with the artists to not work for anyone else, in exchange for gifts and other incentives, thus leading to the symbolical expression of the claim.

* I am using “artist” as a collective term for the engineers, mechanics, craftsmen and other progenies involved in the construction of these architectural wonders.

Fret not, not all’s bad and sad:

Raja Raja Chola who built the Thanjai Periya Kovil (Brihadeeshwara Temple) gifted the workers involved in its construction with countless gifts and incentives, at times said to have personally solved their socioeconomic problems.

I could go on about why this temple is an architectural wonder, but I shall save it for another post. It seems that I had drifted far from what I had wanted to share, thus I feel obliged to take a swift turn back to square one.

Let’s focus on ancient architectural techniques used by commoners.

The Ancient 3-Step DIY to building your OWN Monument. Slaked lime + Palm toddy + Jaggery = House

This story has been passed by the word of mouth, thus I do not have any sources to cite, and it is due to my mother’s knowledge of personal experience that I received this valuable information.

Slaked lime, or Sunnambu (சுண்ணாம்பு)

In early Southern India, perhaps even till the late nineties, sunnambu (slaked lime, often pink), karuppatti (palm jaggery) and padhani (palm toddy) were used to construct houses. From chettinadu houses to forts, sunnambu was the go-to indestructible rock that would be placed in a sunnambu kalvaai. Folklores mention the British forces unable to destroy the house of Kattabomman (a freedom fighter), only successful after numerous tries.

You can picture sunnambu kalvaai simply as a public space designated to the breaking down of sunnambu rocks into smaller, constructible pieces. The slaked lime rock is placed on it, and with two farming cows tied to it on opposite ends, and they move in a singular direction as the lime breaks, with (obviously) the timely addition of water. Each block of sunnambu after the process is far bigger than a single brick, they measure to about 5 to 7 inches wide (you’d be able to spot them in huge forts).

Because the slaked lime blocks are so huge, the pillars of the house turn out big, and my mother recounts about how they’d always had to play around the pillar, and not past it. They also produce powder from the rocks (சுண்ணாம்பு தூள் சரித்தல்).

Sunnambu is soundproof and hard, you would not want to flick even a finger on it. Meanwhile, the walls of my house are so hollow, I can hear my knock past rooms.

Palm toddy, or Padhani/Padhaneer (பதநீர்)

Padhaneer has always been made as a drink, and if well-churned, forms karuppatti, or palm jaggery. This has been used in the construction of many South Indian Hindu temples keeping the structures rigid for centuries.

Palmyra Jaggery or Karuppatti (கருப்பட்டி)

It is rather unfathomable to hear that sugar, of all things, is used to build structures. I am not exactly sure on how it was used, but it was fascinating to learn of this fact alone.

There may have been more condiments to the above process, that I may be unsure of.

Living with Nature

The use of Lotus.

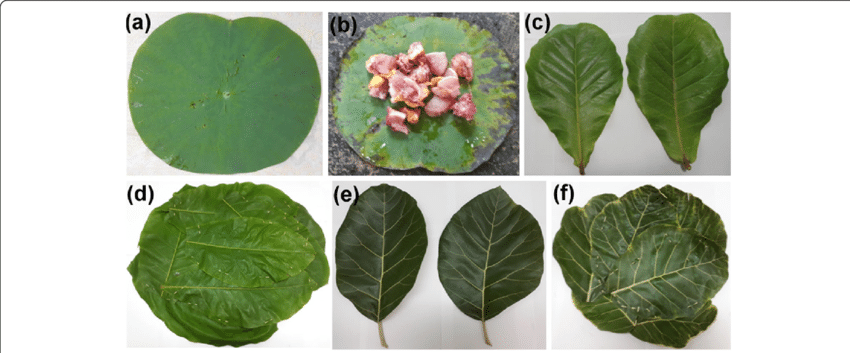

The lotus finds its relevance in many Asian cultures, most notably the Chinese and Indian ones. Lotus leaf rice is a common Chinese delicacy, but what I had not known was that similar to the banana leaf, the lotus leaf (sun/air dried) was extensively used in olden Tamil Nadu. The reasons behind the use of lotus leaf as a plate was simple- it was eco-friendly, disposable and held many great benefits, just like the banana leaf.

In the past, wooden cupboards were common. However, to place the wardrobe on the walls would be foolish, because when it rained and the inner walls (made with cement) soaked the water dripping from cracks on the roof, or simply from the open air-courtyards, the wood will begin rotting and its durability is compromised. Tamilians instead fixed dry lotus leaves onto the wall, and then place the cupboard. The lotus leaves are waterproof and huge, and prevent the moisture from the walls from seeping into the cupboard.

The Lotus stem and leaves are used in traditional (non-allopathic) medicines, and its flowers are used as accessories or offerings to the Deities (used in religious rituals, etc). My mother shared that villagers would often willingly grow lotuses (along with lilies) in ponds and lakes, for they helped in the conservation of the local reservoirs, ensuring a steady supply of water for the village. The large, flat, lotus leaves act similar to that of black balls (shade balls), preventing the growth of algae, or the rapid drying up of lakes. I asked my mother—how about the resulting lack of sunlight entering the waters, that pose a threat to underwater lives?

Her response was that the little gaps between the leaves did allow for sunlight to enter the water bodies, unaffecting the marine life thriving beneath the lotuses.

The use of palm leaves

Palm leaves, called pana olai (பனை ஓலை) are repeatedly hit against a hard surface and tapped on with a stick to produce a brush like texture of the leaf. They were used to paint houses, long before conventional brushes gained popularity.

They are also used to make leaf plates at times, along with Sal leaves, banyan tree leaves, banana and lotus leaves.

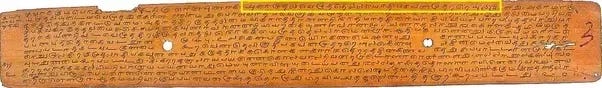

Palm leaves are also commonly known for functioning as paper for ancient Poets, Wise men, Teachers and Spectators of Great Epics. The Tamil Literature is filled with millions of poem verses, some serving as moral books, some simply as an expression of passion from daily lives, while some as a recount of the Greatest Tamil epics.

Obviously being great craftsmen, the Tamils found every other way to use the palm leaves (along with coconut leaves), to knit from baskets to beds, to even huge shelters for rituals and processions, such as marriages, puberty functions and funerals. You can spot the sight predominantly in villages. Palm leaves are folded into 1-2 inch deep saucers for drinks and wrapped to cook steamed dumplings.

There are countless other plants that the natives have incorporated into their daily lifestyle, but if I had to mention one other starkly important tool, then it’d be the use of Neem Sticks as toothbrushes.

Thus, we shall end the post blissfully and gratefully here, upon receiving the blessings of heaven descended superstar neem sticks :p

That’s all folks! :D

Adios.